The Man Out Front

An article, originally published in Contrast (The Television Quarterly) Spring 1962, on the appeal of Bruce Forsyth, already the virtuoso master of ceremonies and all-round showman, who would go on to entertain us for seven decades.

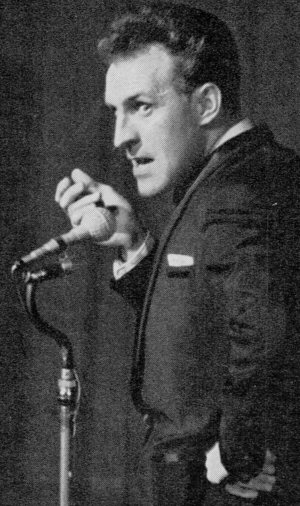

His favourite image of himself was supplied by one of the critics: The cheeky boy on the bacon counter, he called me. I loved that! It's a family joke now! If Penny, that's my wife, if Penny catches me trying on something, teasing her, she says, "There's that cheeky boy on the bacon counter again!" Another critic called me television's end-of-the-pier comic. I like that, too! The end-of-the-pier comic has to work hard on his audience, make them feel they're all having fun together, having a good time! I've always tried to do the same with the Palladium audience, I mean all the viewers at home, make them feel they're really there.'

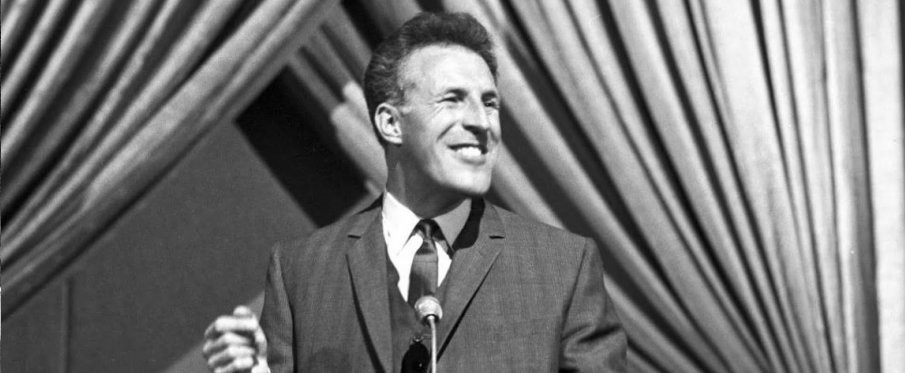

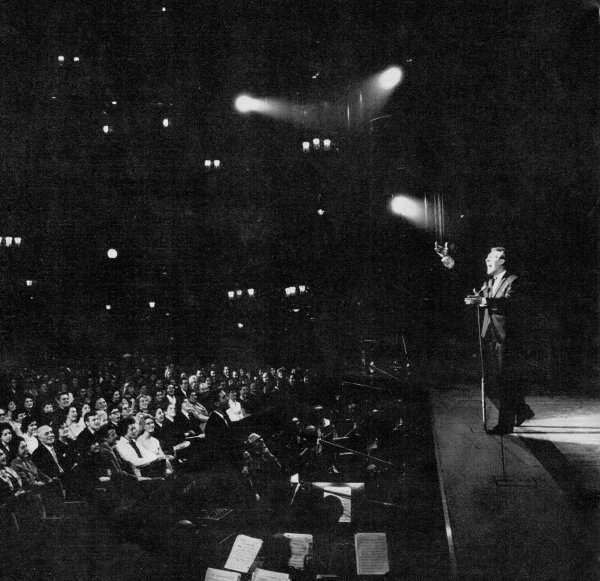

After two and a half seasons as compere plus half a dozen guest appearances, Bruce Forsyth personifies the spirit of Sunday Night at the London Palladium, which in turn represents the essence of commercial television, at least in the eyes of Val and Lew. It's munificent, imperishable, extravagant, the summit of show biz, yet friendly with it. And it's all free, Val Parnell's bounty for loyal viewers. Cheerful, quick-witted, bouncy, organizing, unfailingly enthusiastic, Forsyth embodies more successfully and more likably than anyone else the role of Entertainer to the Welfare State.

He might have been prepared for the job by a kindly fate. His early career included three spells at the classic nursery, the Windmill. Though Forsyth, unusually among Windmill veterans, says that although the audience could sometimes be responsive and matey, like a forces' audience, playing to three furtive girl-hungerers on a June afternoon remains an iron test of a comic's egotism. Forsyth did a patter act interspersed with songs and impersonations, took part in occasional sketches, even danced. The routine he revived with Penny in the last Palladium show before Christmas was one they had done together at the Windmill where she was a soubrette.

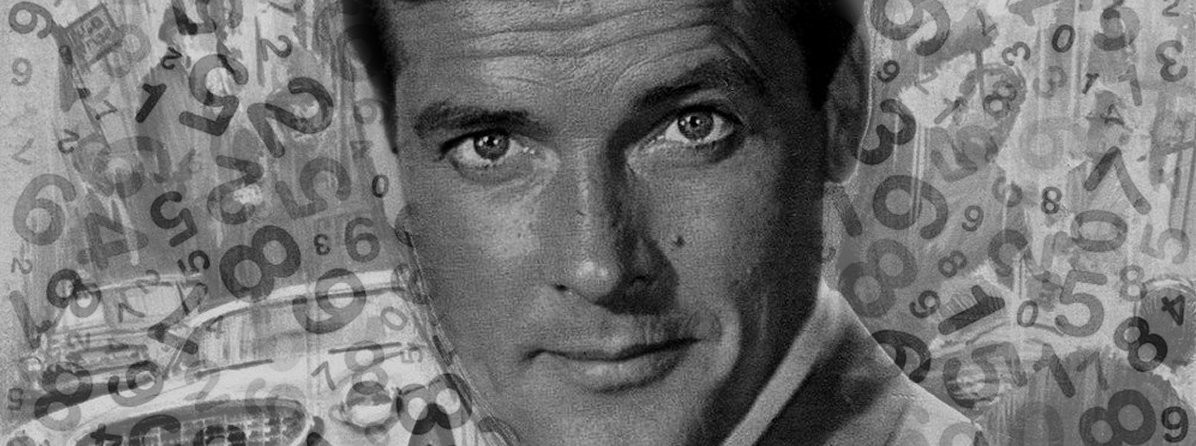

In the RAF he got up a jazz group, adding to an already formidable versatility. He plays the piano, the drums and almost any other instrument, writes his own songs. Finally three consecutive seasons, not literally at the end of a pier, but in the little seaside theatre at Babbacombe, Devon, trained him for the Palladium's Beat the Clock interlude. Weekdays the company did a normal show; on Sundays, because of the Observance laws, they substituted plain-clothes 'concerts'. To fill in time Forsyth used to run interminable audience participation games. `We gave away tea-caddies, things like that, worth about 7s. 6d. I used to say to the winners, "If you were on the telly this would be a washing machine," but I never dreamed I'd be doing it myself on TV one day.' The day wasn't far off.

Forsyth had a feeling that 1958 was a special year for him, a break-through year. Bernard Delfont was already taking an interest in his work; through Delfont, the Grades; through the Grades, ATV. At first the idea was for him to have his own show, or anyway a part of a show. The alternative of the Palladium was offered quite late on. Forsyth had to choose, opted for the Palladium because it was already a going concern. The contract was at first for four weeks, then eight, then twelve, then the whole season. A second season followed, 1959-60. In 1960-61 he made only guest appearances and the ratings fell off (so incidentally did Armchair Theatre's, because it followed the Palladium).

Clearly, Forsyth was indispensable, at least in the all-important Autumn quarter. He returned last September for a reported £1,000 a show. Five years ago he had never earned much more than £1,000 in a year, out of which he had to pay the expenses of his act. Today his income is anyone's guess. The Forsyths take simple pleasure in their affluence, like kids in a gingerbread house. Just now they're discovering food. Penny, who used to exist at the Windmill on cups of tea and onion sandwiches, says that you only start to have a palate at thirty. Forsyth's inclines to sweetness: favourite aperitif, Gin and Italian, complete with cherry; favourite wine, Mateus Rose. Thirty-four this month (February) he is greyer than he looks on the screen, also more elaborately coiffed; his nose and chin are extravagantly Wellingtonian. He likes success, though not adulation (a private visit to Ulster had to be practically abandoned). He wishes people wouldn't want to tell him funny stories.

Good evening, ladies and gentlemen,

Welcome to the London Palladiyum.

It's half-past eight, I’m feeling great,

Val Parnell has booked the date …

Forsyth's habit of breaking into doggerel song for his introductions sums up as well as anything his confident but respectful tenancy of the Palladium show. As with the lucky catch-phrase he hit on almost immediately, 'I'm in charge', there's the element of cheeky-boy cockiness, the glee at being the centre of attention; at the same time the forelock is prudently touched towards the eminence in the wings. To Val Parnell he must have seemed like a long-lost son.

It's easy now to forget how in its first two years SUNDAY NIGHT AT THE LONDON PALLADIUM was identified completely with Tommy Trinder. His square-rigged dinner jacket, irremovable trilby hat and brisk but unsympathetic talent for ad-libbing set the style of the show. If it wasn't actually a pre-war style it certainly wasn't later than the 'forties in flavour. Trinder was a mainly verbal performer with nothing visually funny about him. His manner was aggressively public-bar, aggressively masculine. The appeal was to the older viewers, the ones who could remember the war, the music-hall, the posters that went up all over London, If it's Laughter you're After, Trinder's the Name.

But a wider audience than that needed to be wooed, younger and — as the ITV network spread — less London-minded. At the same time the composition of the Sunday night bill was changing. Traditional music-hall acts were becoming fewer. Their places were taken by Spanish dancers (increasingly popular as more and more people holidayed abroad), middle-brow performers like Adele Leigh, and of course the spate of ephemeral new pop singers. According to a cutting dated early in 1959 someone called Rosemary June was the supporting star of the show on the strength of a single record. Who was she and what on earth became of her? It was implicit, even if no one consciously framed the sentiment, that a new kind of compere was needed for a new kind of show. After a year of short-term tenures, including a refreshingly irreverent six weeks from Robert Morley, Forsyth fell into place as if he'd been machined to fit. The chin and the cheerfulness misled a few critics into thinking he was a straightforward Trinder substitute, but not for long. Forsyth is contemporary and looks it. His dinner suit is as shiny, spidery, short in the jacket and tight in the trousers as Cliff Richard's. He can greet the latest recording idol as someone from his own world. Yet he flatters his older viewers with his awe for their idols (e.g. Gracie Fields); he is never short of awe. He mixes easily with the visiting Americans the Palladium still lures, and his stock is high among them. ‘I've heard so much about you, young man,’ boomed Sophie Tucker.

His manner, compared with Trinder's, is warmer, more sentimental, much more plastic — an object lesson in Welfare State demotic. In private or introducing a posh act (Markova, for instance) he'll speak `normally', dropping down to chat with the house audience the idiom and the aitches tumble in sympathy. ‘Blimey, 'e looks 'appy, don't 'e?’ With a woman Beat the Clock competitor he's playful, almost skittish, calling her `dear' and whoopsing if she makes a mistake; with the man he's matey and reassuring: ‘You've got steady 'ands, 'aven't you? How long you been married? Seven years! Blimey, seven years and still got steady 'ands.’

More than any of his predecessors he gets into the act, not just on the grand scale, as when he and Norman Wisdom made up the whole show, but all the time, in every way. The visiting stars accept it, the audience expects it. In Beat the Clock he skedaddles from side to side, offering wild encouragement, never-minding, helping out, retrieving balls, braking and turning with the comic's traditional knees-up exaggeration. If a rhythm group like the Shadows are engaged, sooner or later there's an extra player on the end of the line, the long face solemnly, marvellously transformed by a pair of horn-rims. After the Spanish dancers there's always a kidding postscript, if only for a few seconds, Forsyth tramping up and down in a poker-faced zapateado. He is, in every sense of the word, a fool; licensed — indeed expected — to play the fool at all times.

Thank-you, Penny,

Thank-you, darling,

Thank-you, sweetheart,

You've made my night.

When we get home to the kids, dear,

I hope they'll think that we were all right.

And so on ad nauseam, to the tune of Mac the Knife. It closed that last edition before Christmas and it sums up the more distressing side of Forsyth's public character: sentimental, gushing, full of reverence for show business in general and the Palladium in particular. Introducing Cliff Richard: ‘We're so proud to have you, Cliff . . . .’ Signing off the show, any time: ‘And next week the jackpot will stand at five . . . hundred . . . pahnd.’

Despite his association with the last stronghold of Variety, Forsyth has long hankered to break into the modem musical. His pantomime in Manchester last Christmas was almost a musical, he claims. His summer show at the Palladium this year will be even closer. Soon he may achieve the real thing. And for the time being SUNDAY NIGHT AT THE LONDON PALLADIUM is in other hands and Forsyth contents himself with a six-day, six-night week. But it seems unlikely, at the very least, that such a compatible association is over for all time.

Article: Philip Purser

Philip Purser is a British television critic who wrote for The Sunday Telegraph from its launch in 1961 until 1987. Also a novelist, Purser co-authored two editions of Halliwell's Television Companion and wrote Peek-A-Boo - The One and Only Phyliss Dixey, for Thames Television in 1978.